Mental Imagery in Iaido

You may have seen a famous heptathlete internally rehearsing her technique for the high jump just as she’s waiting to run up to the bar. She rolls her hands rapidly, presumably translating her steps into that movement, rolls her eyes, arches her back a little in a facsimile of the Fosbury flop she’s about to execute. You may have seen a perma-tanned diver, just before a 10m high board dive, rolling his hand the precise number of times he’s going to spin, arch his back out and raise his hand above his head into a sharp point. What exactly are they doing? They’re using mental imagery to rehearse and improve their performance. Yes, mental imagery is a very powerful tool that can improve performance and is used widely by elite sports people. By mentally rehearsing a routine, athletes can prepare themselves to achieve the best performance when they need it most and build their confidence for a competition or a promotion grading. It is a useful aid when an Iaidoka is perhaps laid off with an injury and cannot practise and can even help diverting their attention from the negatives of their situation. Mental imagery can be used whilst travelling, or even when waiting for sleep to come over you last thing at night. Elite athletes, use mental imagery more than any other performance-enhancement technique.1 It is a potentially complex process that must be well-understood to optimise it’s benefits. Mental practise is the repetition of a task, without observable movement, with the specific intent of learning.2

Definitions of Mental Imagery

There are broadly two perspectives to mental imagery: internal and external. Internal imagery requires an approximation of the real-life scenario such that the person imagines being inside their body and experiences the sensations which might be expected in the actual situation. For example, if you were imagining performing Shohatto, you would be looking out through your eyes, you might feel the tension in your thighs as you bring your knees together and rise, simulataneously pushing the tsukagashira forward and feel the tightening of your koyubi, kusuriyubi (little and ring fingers) liberating the blade the blade into nukitsuke etc. In external the practitioner observes themselves from the outside like viewing a video of oneself performing the kata. You might see the intense look in your face, the way you keep your chin a little dropped and your neck craned forward and you make a decisive cut across the face of teki. You see your hips are square but your torso is reaching forward at the shoulder etc.

Now the temptation may be to believe that when using internal imagery, one has a better ‘kinesthetic’ perspective of the movements, but in fact this is not the case and both modalities of imagery have similar kinesthetic qualities since they are both generated within one’s imagination.3

One of the keys to effective use of imagery and to refines one's motor performance is to make the imagery as vivid and complete as possible utilising multiple sensory modalities from proprioception, touch sensation, auditory, visual, olfaction etc. This will take practise and initially one may find the pace of the rehearsal is slow compared with the real-life movement. This si normal and with more rehearsal practise one will find it easier and the rate will become almost identical to real –life performance.

The Four Ws of Imagery Use

These are- Where imagery is used, when imagery is used, why imagery is used and what is being imagined.

Where?

This related to the context of imagery use within training and performance activities. Elite athletes tend to use imagery in competition environments more regularly than in practise situations.4

When?

This refers to the timing od imagery use. This is determined in relation to scheduling factors such as within or without of physical practise or training time; before during or after competition or as part of rehabilitation.

Why?

Represents the functional aspects of the imagery use.(ibid)

What?

What is actually being imagined and the context of effectiveness, nature of imagery, surrounding, type of imagery and controllability.

Forget the boring psychology, here’s the neuroscience!

Mitori Geiko

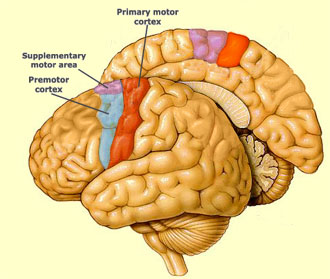

Mirror neurones were first discovered in the early 1990’s in the premotor cortex of the rhesus macaque monkey.

Human premotor cortex where mirror neurones are found.

These are special visuo-motor neurones that were found to discharge action potentials (electrical signalling impulses) when the monkey actually executed an action, as well as when they were watching the same movement being performed by another monkey or on video. The monkeys were allowed to observe a physical movement in order to learn the pattern, visually. In order to do so, they will have had to transform the observed visual information into actual motor commands. This is as ‘visuo-motor transformation’. Studies show that observational motor learning may improve action perception and motor execution. Moreover, action-perception and action-execution interacted in a mutual and bi-directional fashion (visuo-motor and motor-visual interaction), suggesting that perception and action share common neural mechanisms. Mirror neurones have been proposed as the neurophysiological basis of the visuo-motor and motor-visual transformation processes, and may play a role in the perceptual and motor improvements induced by observational motor learning. From this, it might be possible to infer that internally generated motor imagery may act upon the mirror neurones of the premotor cortex just as real visual observation does and similarly, ‘imaginary-visuo-motor transformation’ may be taking place to rehearse and improve one’s performance!

How to Practise Mental Imagery

1. Have a complete understanding of how the kata is supposed to be performed from your practise repetitions, from your notes, hand books etc. Really know your kata and make sure you have actually performed it many times.

2. Find a comfortable place to sit or lie down, somewhere you can spend quite some time, comfortably.

3. Spend a few minutes relaxing, off-loading any extraneous thought, perhaps by mindfully counting your breaths for a few rounds (‘susokukan’).

4. Begin your imagery ensuring you are making the experience as complete and rich as possible including as many senses as possible. Feel the kata as completely as possible with big, full-range motions even if in life a particular movement is slightly unpleasant to perform – in your mind, there is no pain!

5. When you have finished your performance, relax take a few relaxing breaths and reflect on any areas that might require deeper and fuller imagination.

6. Repeat your imagery keep the modification in mind and perhaps slow down when you get to that part of your reply.

7. Repeat about ten times and stop and relax for a few minute before moving onto to doing something else.

Do not overdo things. Build-up your imagery skills until they feel natural and you can include more kata into a session.

References

1. Defrancesco, C & Burke, K.L. (1997)Performance-enhancement strategies used in a professional tennis tournament. International Journal of Sports Psychology 28: 185-196.

2. Corbin, C.B., Mental Practice. In Ergogenic aids and muscular performance, ed Morgan W.P. 94-118. New York: Academic Press.

3. Gates, S.C., Depalma, M.T. & Shelley, G.A. (2003) An investigation of the relationship between visual imagery perspectives, kinaesthetic imagery and locus of control. Applied Research in Coaching and Athletics Annual 18: 145-164.

4. Munroe, K. Giacobbi, P.R., Hall, C.R & Weinberg, R. (2000) The four Ws of Imagery use: Where, when, why and what. Sports Psychologist 14: 119-137

40 Years of Budo!

Comments

Post a Comment